“People who do not know the Lord ask why in the world we waste our lives as missionaries. They forget that they too are expending their lives … and when the bubble has burst, they will have nothing of eternal significance to show for the years they have wasted.” – Nate Saint

His Early Life and Times

Like many young men in the first half of the 20th century, he was fascinated with airplanes. In 1930, at the age of seven, one of his older brothers gave him a ride on a plane. Three years and some thrilling flights later, his brother let him take the controls on a flight. From that time on, he was fascinated, not only with airplanes; he became fascinated with flying.

In 1942, at the age of 19, Nate enlisted in the U.S. Army where he expected to become a pilot during World War II. Unfortunately, due to a lingering infection, the Army would not allow him to fly. Nate turned that into an opportunity to become an aviation mechanic. He learned valuable lessons in that position that he would use later.

His Unexpected Life in Aviation

Following Nate’s three years in the military, he obtained a commercial pilot’s license and enrolled at Wheaton College. During that time, his father made him aware of the newly established Christian Airmen’s Missionary Fellowship (CAMF) which eventually became the Mission Aviation Fellowship.

The MAF began transporting missionaries into hard-to-reach places in the jungles of Mexico, Peru, and Ecuador. While at Wheaton, Nate committed his life to serving the Lord as a missionary and missions pilot. He so with the understanding that the work would be dangerous. In one year alone, 51 people died in missionary plane crashes in the jungle. In 1948, Nate and his wife traveled to Ecuador to open an MAF base at Shell Mara.

His Eventful Life in Ecuador

Missions work in Ecuador did not start well for the avid missionary pilot. In December of his first year, the plane he was piloting crashed after a powerful downforce of wind drove it into the ground. Nate suffered a broken back and other injuries that kept him in a body cast for six months.

Nate solved one of the early problems in jungle missionary aviation while serving the Lord in Ecuador. Pilots would drop supplies in predetermined locations, but some supplies were destroyed when the hit the ground, and more ended up in the treetops of the jungle canopy. Nate devised a method of safely and efficiently lowering supplies using a bucket and a rope while circling overhead. Not only were the supplies delivered, but the missionaries were able to send messages and other items up to the plane using the device.

Nate described his life in Ecuador this way:

“It is our task to lift these missionaries up off those rigorous, life-consuming, and morale-breaking jungle trails—lift them up to where five minutes in a plane equals twenty-four hours on foot. The reason for all this is not a matter of bringing comfort to the missionaries. They don’t go to the steaming, tropical jungles looking for comfort in the first place. It’s a matter of gaining precious time, of redeeming days and weeks, months and even years that can be spent in giving the Word of Life to primitive people.”[1]

His Eventual Loss in Ecuador

Nate and four other missionaries had developed a burden to reach the Aucas, a reclusive tribe of native Indians known to kill others found in their territory. The Ecuadorian government had been considering sending troops in to subdue the natives.

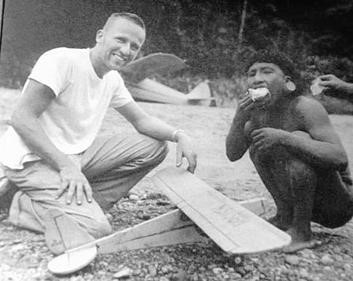

Nonetheless, Nate, Jim Elliot, Ed McCully, Peter Fleming, and Roger Youdarian began an effort to break through to the tribe. They started by making flights over the village, dropping gifts from pots and pans to trinkets. Having received what they considered a warm response, they determined that it was time to meet the Aucas in person.

On January 8, 1956, the five landed the plane on a strip of side alongside a river near the village. They were to make scheduled radio calls to their families back at the airfield compound, but no transmissions were ever made. The Aucas had massacred Nate and the others and left their bodies in the river and along the beach.

The story made major headlines, including an entire photo spread in Life magazine.

His Eternal Legacy

Jesus said that “even the gates of Hell shall not prevail” against the Kingdom of God and His Church. Indeed, the spears of the Aucas could not. Instead of retreating in fear and defeat, the effort to reach the Aucas continued, including the personal ministry of Nate’s son Steve and sister Ruth and Jim Elliot’s wife Elisabeth, each of whom eventually lived with and ministered to the Aucas.

Their continued work has created an eternal legacy as many of the Aucas natives have accepted Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior over the years, including six of the men who participated in the raid and killed Nate and his fellow missionaries.

The Indians told their families that they were puzzled at why the men did not fight but willingly gave up their lives. Their amazement opened the door for the women to tell them that the men were there to tell them about Jesus Christ who “freely allowed his own death” to ransom them from sin and its inevitable price.

Rachel Saint spent the rest of her natural life with Wycliffe Bible Translators among the Aucas and is buried in Ecuador.

Kimo, the pastor of the tribe, requested the honor of baptizing Steve and Kathy, Nate’s children, to demonstrate their reconciliation through Christ. The pastor had been a member of the killing party.

Gikita, the leader of the attack, died a believer at the age of 80. He said that he was “eager to go to Heaven and live peacefully with the five men who came to tell them about Creator God.”[2]

As Nate Saint said, “When life’s flight is over, and we unload our cargo at the other end, the fellow who got rid of unnecessary weight will have the most valuable cargo to present to the Lord.”

[1] Jungle Pilot: The Life and Witness of Nate Saint, Russell T. Hill, Copyright 1959 by The Fields, Inc,, Harper Collins Publishers, Inc.

[2] Even Unto Death: Wisdom from Modern Martyrs, edited by Jeanne Kun, The Word Among Us Press, 2002.