WILLS POINT, TX – Gospel for Asia (GFA World and affiliates like Gospel for Asia Canada) founded by KP Yohannan, issued this Special Report update on winning the ancient conflict against the mosquito and vector-borne diseases.

It’s small, this little welt on my hand or the bump behind my ear. The welts come and go and are a minor annoyance during the spring, summer and fall when I am gardening or when my husband and I host outside gatherings or when the grandchildren come to play and explore the path through the woods their grandfather cut for them. These seasons are when mosquitoes buzz in the air and wait to strike humans for the blood the females need to nourish their eggs.

It is a little distraction; I bat away the pesky critter or slap it when it sucks my blood, causing a splat on my own skin. The bump caused by this bite swells and itches, but I’ve learned the more I scratch, the itchier the welt becomes.

When a mosquito bite breaks the skin, my immune system sets off a warning; the mini-wound is instantly flushed with increased blood flow and my white-blood-cell count elevates slightly. This reaction causes the swelling; it is really an allergic reaction. On the micro-scale of things, this physiological response is instantaneous. For most of us, a mosquito bite, or multiple bites, is an annoyance causing us to itch, then scratch, and finally, if the bites continue to annoy, seek some kind of salve to soothe and a repellant to prevent.

In some places in the world, however, a mosquito is no small thing. It can bring on fevers, illnesses, work displacement and even death—causing thousands of families sorrow.

In my original special report for Gospel for Asia titled It Takes Only One Mosquito, I explored the impact of faith based organizations on modern medical approaches. This update explores the ancient and ongoing battle between man and mosquitos which transmit vector-borne diseases.

Know Your Adversary or Fall Victim to Vector-borne Diseases

Knowing your enemy is well-known advice attributed to Sun Tzu’s ancient Asian manual The Art of War, which is part of a syllabus for potential military-service candidates. Its recommendation for warriors is certainly appropriate for the equally ancient conflict that exists in many parts of the world between Man and Mosquito. In reality, where I live the welt on my hand may be small and annoying but for whole population sectors around the world, the negative impact of mosquitoes and the diseases they may transmit is overwhelmingly huge.

So let’s take Sun Tzu’s advice and get to know our enemy:

The most common, and most dangerous, are the various species in the Culex, Anopheles and Aedes.

Mosquitoes can live in almost any environment, with the exception of extreme cold. They favor forests, marshes, tall-grass and locales, and ground that is wet at least part of the year. Incredibly, Arctic tundra is a great breeding-place for mosquitoes—the soil that has been frozen all winter thaws in the warming weather, rendering these vast acres huge mosquito incubators. These insects must have water to survive (breeding can occur in as little as one inch of standing water), so areas that border ponds, lakes or puddles are essential to their spread and survival.

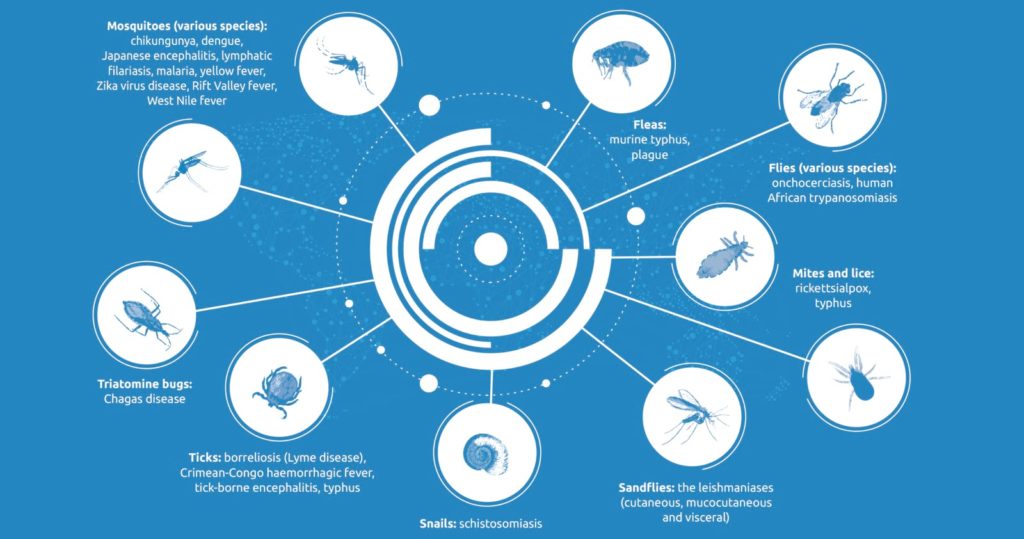

Categorized among the group known as “blood-feeding arthropods” which also includes ticks and fleas, mosquitoes are responsible for a wide range of diseases that result in various symptoms such as fevers, rashes, aches and pains, vomiting and death. The World Health Organization classifies such illnesses as “vector-borne diseases,” which are “human illnesses caused by parasites, viruses and bacteria that are transmitted by vectors.”

The WHO’s report on vector-borne diseases

includes these stunning facts:

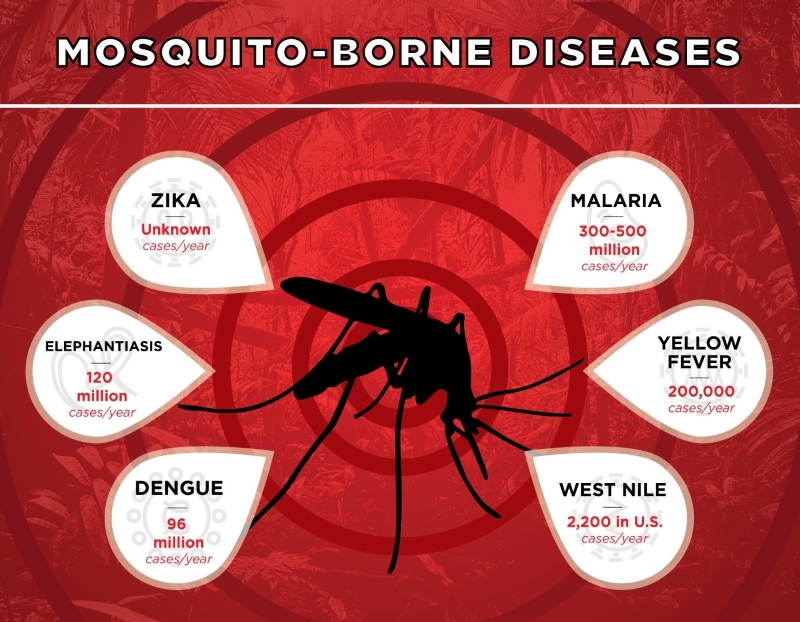

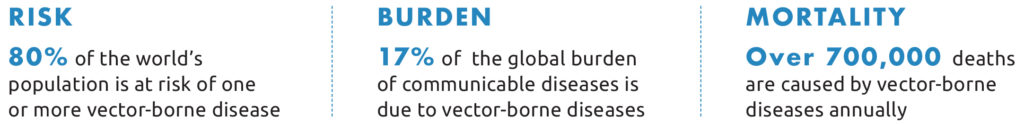

- Vector-borne diseases account for more than 17 percent of all infectious diseases, causing more than 700,000 deaths annually.

- Malaria is a parasitic infection transmitted by Anopheline It causes an estimated 219 million cases globally and results in more than 400,000 deaths every year. Most of the deaths occur in children under the age of 5 years.

- Dengue is the most prevalent viral infection transmitted by Aedes More than 3.9 billion people in more than 129 countries are at risk of contracting dengue, with an estimated 96 million symptomatic cases and an estimated 40,000 deaths every year.

“Other diseases transmitted by vectors include chikungunya, Zika, yellow fever, West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis (all transmitted by mosquitoes) and tick-borne encephalitis (transmitted by ticks).”

Other Odd Facts in the War on Mosquitoes

These vectors can transmit infectious pathogens between humans, or from animal to humans. Mosquitoes, as mentioned, are blood-sucking insects; when doing so, they can ingest pathogens from a host and transfer it to another host once that pathogen begins to replicate. Often, once a vector becomes infected, it is capable of transmitting the pathogen for the rest of its life, becoming a flying, one-insect, disease-delivery machine.

According to the WHO, 700,000 people die each year from malaria, dengue, Japanese encephalitis and other vector-borne diseases.

“The burden of these diseases is highest in tropical and subtropical areas, and they disproportionately affect the poorest populations,” writes the WHO.

“Since 2014, major outbreaks of dengue, malaria, chikungunya, yellow fever and Zika have afflicted populations, claimed lives, and overwhelmed health systems in many other countries. Other [vector-borne] diseases … cause chronic suffering, life-long morbidity, disability and occasional stigmatization.”

Perhaps that little bump growing on my hand after a summer mosquito attack is not such a little thing after all.

Mosquito Abatement: Part of Caring for the Least of These

In light of what we know now about that enemy, the mosquito, is it any wonder that mosquito-abatement programs sponsored by faith-based organizations like GFA World are one of the evidences that fulfill this Gospel imperative: “Love your neighbor as yourself”?

I love the story on GFA’s website reporting how GFA workers distributed some 9,000 mosquito nets to students living in hostels, now away from their families. Two nets were given to each student, one for them to use and one to send back home.

“I am thankful for the mosquito net,” said Marcus, a ninth-grade student. “I am from a poor family, and there is no one to meet my needs.”

On a broader scale, GFA World has delivered nets to thousands of families in need and held awareness training and awareness programs in many affected areas. In Odisha, a state greatly affected by various vector-borne , GFA workers led mosquito awareness programs and gave nets to 2,050 impoverished families, including people at a district medical hospital. In the tea-growing state of Assam, GFA workers conducted awareness training about the need for prevention, distributing 2,000 nets to tea-garden employees.

To date, GFA World has distributed more than 1,300,000 mosquito nets in malaria-prone areas of South Asia to protect people from life-ending vector-borne diseases.

The world’s largest grassroots campaign to protect people from malaria is the United Nations Foundation’s Nothing But Nets campaign. Aiming to be the generation that defeats malaria, Nothing But Nets brings together UN partners, advocates and organizations worldwide to raise awareness, funds and voices to protect vulnerable families from malaria, given that every two minutes a child dies from malaria.

Mosquito nets, as part of a general abatement program in many countries of the world, overcome one of the major deterrents to all of the above: the small, seemingly innocuous welt on the hand, behind the ear, on the ankle or calf. A mosquito bite.

Other Means of Mosquito Warfare

Local and global management of mosquito-borne viruses, many without a vaccine to prevent or a cure to stop the progression of disease, must rely on preventive as well as palliative measures.

First, there are protective measures individuals can practice while traveling to or living in mosquito-compromised territories. For instance, local home-dwellers can start by emptying any containers filled with water that are lying around the yard, house or apartment, or in alleys or garbage-collection centers. Tip over that plastic swimming pool and fill it again when needed. Dump any bowls outside that pets feed from. Some out-of-door containers can have holes punched in their bases so that water drains. Clean rain gutters so they don’t become clogged with leaves or debris, which inhibits rainwater from draining and leaves it to pool for days. These practices prevent mosquitoes from breeding in standing water.

Many of these abatement methods are a matter of paying attention and using common sense regarding standing-water sources. For instance, keep grass mowed, trim back bushes and rake up fallen leaves. These are all places where mosquitoes like to hide and breed. Some recommend that any low-lying depressions in a yard should be filled since they will hold water after lawn irrigation or rain. Swimming pools, of course, need to be kept clean and chlorinated. Stocking any small ponds with fish can deter mosquitoes, as fish eat mosquito larvae. As a last resort, for swarms of mosquitoes, spray insecticides.

This, of course, raises its own problems, since most foggers or sprays carry warnings in bold language on their labels. The possibility of unintentional user-poisoning from these highly lethal compounds is evidenced by the cautionary statements on them. For personal protection, a variety of DEET-free (diethyltoluamide) organic repellants are on the market. Many are safe to use around children. In our modern, chemical-wary society, various natural approaches to combating mosquito hoards are recommended, including growing plants that repel mosquitoes. The smell of marigolds, lavender, sage, rosemary and lemon Thai grass make them ideal candidates. A sprig of fresh rosemary placed in water for a few minutes and then placed on a hot grill is recommended as a natural repellant. In addition, pots of basil, bee-balm, catnip or citronella placed in patio or outside seating areas help reduce mosquito colonies.

For travelers, or people living in high at-risk areas like South Asia, a series of personal techniques can be utilized to combat the potential for mosquito bites. These include the following:

Get vaccinated for diseases like yellow fever and Japanese encephalitis. For all other mosquito-borne diseases, which do not have vaccines or medicines, the key strategy is to prevent mosquito bites.

Cover up with long-sleeved clothes and pants when you’re out and about, especially at dusk or night when you have the greatest risk, and avoid bright clothing.

Burn mosquito coils under your dinner table while sitting or eating outside.

Whenever possible, use insect repellant that’s approved as safe and effective.

Use window or door screens to keep mosquitoes out of your house.

Sleep under a mosquito net at night.

Photo by WHO/HTM/GVCR/2017.01 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO)

Since so many of South Asia’s poorest families cannot afford insect repellant, window screens or long-sleeved clothes, it becomes essential for non-profits like GFA World to provide the mosquito nets that will at least keep them safe at night.

A Memory from My Childhood of the “Big Ditch”

Long ago, as a schoolgirl, I was assigned to read a book titled Mosquitoes in the Big Ditch. This is the historical account, in children’s literature, of the opening of the Panama Canal, which finally took place after great failure and much loss of life.

The Panama Canal cuts across the isthmus that joins Panama to Costa Rica at its north and to Colombia at its south. Before its engineering, ships needed to traverse around the southern coastline of South America, a lengthy journey by anyone’s measurement. The French had attempted to cut through this land mass and engineer the massive trench that would allow ships to cut their sailing route from east to west (or vice-versa) by thousands of miles. However, due to epidemics of malaria and primarily yellow fever, the French finally withdrew, and after two decades of hard labor and $287 million of investment, the canal project was terminated in 1889.

At this point, the United States bought the development rights to the Canal from the now-bankrupt French for a fraction of the cost. In the history of entomological transmission, the Americans were to succeed where many had failed because a handful of scientists proved yellow fever was caused through the transmission of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Before this discovery, the high incidence of infection was attributed to bad water, foul air and disastrous medical-care decisions that allowed the disease to spread.

U.S. Army physician Major Walter Reed finally demonstrated unequivocally that the vector for yellow fever was the Aedes aegypti. A newly-emerged mosquito was allowed to feed on a suffering patient and then bite volunteer coworkers. As predicted, they succumbed to yellow fever several days later. Mercifully, they recovered from the successful experiment.

In 1904, U.S. Chief Sanitary Officer Dr. William Gorgas took on the task of eradicating yellow-fever-carrying mosquitoes from the 500 square miles of jungle canal-zone. Some 4,000 workers, thousands of gallons of sprayed insecticide, 120 tons of pyrethrum insecticide powder, 300 tons of sulphur and 600,000 gallons of oil later, the task was done.

It was to be the first of many thousands of such efforts, large and small, that would be conducted down through the decades since mosquitoes were defeated in the Big Ditch. It is a war, unfortunately, that needs to be won and won and won.

And while mosquitoes were momentarily defeated to construct the Big Ditch, the ancient war between man and mosquito still wages on every day in places like South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. And it takes “getting to know the enemy” to fulfill the task of eradicating vector-borne diseases, and protect people from life-ending mosquito bites.

You can help in this effort today by making a donation to provide mosquito nets to people in South Asia at risk of mosquito bites. Your gift of $50 will provide mosquito nets for five families in Asia, and safeguard them from the life-ending diseases that mosquitoes transmit.

The bump on my hand, in its conglomerate potential, is not so small after all.

Save Lives – Give Mosquito Nets

Learn how to your gift protects families in Asia from vector-borne diseases.

About Gospel for Asia

Gospel for Asia (GFA World and its affiliates like Gospel for Asia Canada) is a leading faith-based mission agency, bringing vital assistance and spiritual hope to millions across Asia, especially to those who have yet to hear the “good news” of Jesus Christ. In GFA’s latest yearly report, this included more than 70,000 sponsored children, free medical camps conducted in more than 1,200 villages and remote communities, over 4,000 clean water wells drilled, over 11,000 water filters installed, income-generating Christmas gifts for more than 200,000 needy families, and spiritual teaching available in 110 languages in 14 nations through radio ministry. For all the latest news, visit our Press Room at https://press.gfa.org/news.

Read more news on the Vector-borne Diseases and Gospel for Asia on Missions Box.

This Special Report originally appeared on gfa.org.

Read another Special Report from Gospel for Asia on Mosquito-Driven Scourge Touches Even Developed Nations — Malaria Alone Claims 400,000 Lives Per Year

Read what Christian Leaders have to say about Gospel for Asia.