WILLS POINT, TX – Gospel for Asia (GFA World and affiliates like Gospel for Asia Canada) founded by KP Yohannan, issued a Special Report on the ugly truths of world hunger: “Scandal of Starvation” — world hunger is a long-term social and global crisis, directly or indirectly causing around 9 million deaths each year – more than AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined.

There are many things wrong with our broken world, from prejudice and violence to modern-day slavery. The United Nations has identified 16 top enemies of humankind, with ambitious aims to tame if not defeat them by 2030. But have you ever paused to wonder what subjects top Jesus’s list of great ills?

Hunger is one of them. Shortly before His betrayal, Jesus spoke to His disciples about the coming judgment, when everyone will appear before Him. He told of those who will inherit the kingdom prepared from the foundation of the world, and why.

“For I was hungry and you gave Me food,” he began (Matthew 25:35). He went on to name the thirsty, the strangers, the naked, the sick, and the imprisoned. Meeting their needs was also a reflection of God’s kingdom, He said. But He recognized empty bellies first.

Perhaps that is because it is hard to hear anything else above the rumble of an empty stomach. Words of hope for a better tomorrow—whether practical advice or spiritual encouragement—tend to fall on deaf ears when someone has eaten little or nothing for too long.

Gospel for Asia (GFA) founder K.P. Yohannan said, “If you see a dying man begging on the street, how can you share the Good News with him and not give him something to eat?”

When hunger muffles your hearing, it’s not because of frustration but physiology. When you are hungry, your body starts to do what it can to conserve energy. Like a computer, it shuts down peripheral programs. In the short term, hunger makes it harder for you to concentrate. Over time, it makes it harder for you to understand. You go from not having the desire to learn to not having the ability.

Consider the student faintings last year that became common at the Augusto D’Aubeterre Lyceum school in Boca de Uchire, Venezuela, in the wake of the country’s severe economic crisis. They occurred because so many students went to class without eating breakfast, or dinner the night before, reported The New York Times. At other schools, children wanted to know if there would be any food before they decided whether to go at all. “You can’t educate skeletal and hungry people,” one teacher said. Hence hunger is not just a desperate and immediate personal issue. It is also a long-term social and global crisis, directly or indirectly causing around 9 million deaths each year—more than AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined. One report has estimated the annual impact on the global economy of malnutrition through lost potential and production to be as much as $3.5 trillion, or $500 for every single person in the world.

That is the financial impact of what Roger Thurow, a Senior Fellow on Global Food and Agriculture at The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, has called malnutrition a “life sentence of underachievement and underperformance.” If you ask why some countries remain poor or why development aid isn’t as effective as possible and doesn’t have the impact many think it should, he said, “it’s because so many kids are getting off to a horrible start in life.”

COVID-19 Accelerates Starvation in Asia

The global COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated hunger fears. Lockdowns and stay-at-home orders brought national economies to a grinding halt overnight, sending unemployment soaring, and instantly plunging hundreds of millions of families into survival mode.

At the grassroots level, millions of furloughed day laborers and agricultural workers—the backbone of the workforce in many developing nations—faced the grim threat of watching their families starve.

“These nations are in the hands of God right now,” said Yohannan. “There is a real danger that millions could starve to death.”

In southeast Asia, hundreds of millions of children were immediately at risk, as the lockdown paralyzed entire nations. Huge numbers of street children—estimated at 70,000+ in some cities in Asia alone—had no one to beg from and no one to turn to.

“When a crisis hits, the children are always hit the hardest,” Yohannan said. For more details on this story, go here.

Food Insecurity, World Hunger Are Increasing

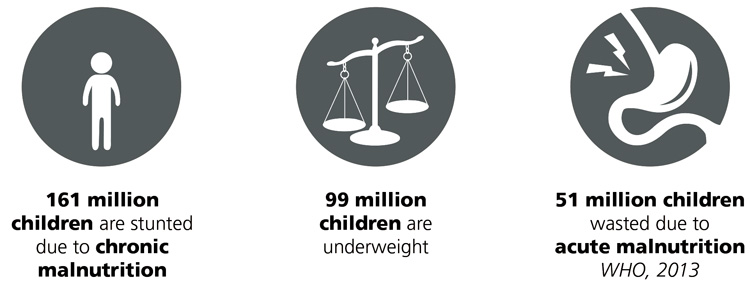

In the measured words of officials and academics, those who don’t have enough to eat are victims of “food insecurity,” not knowing if and when they will eat next or whether it will be enough. The impact of hunger is seen in what they call “wasting” and “stunting,” which describe the different ways lack of food keeps someone from developing physically as they should.

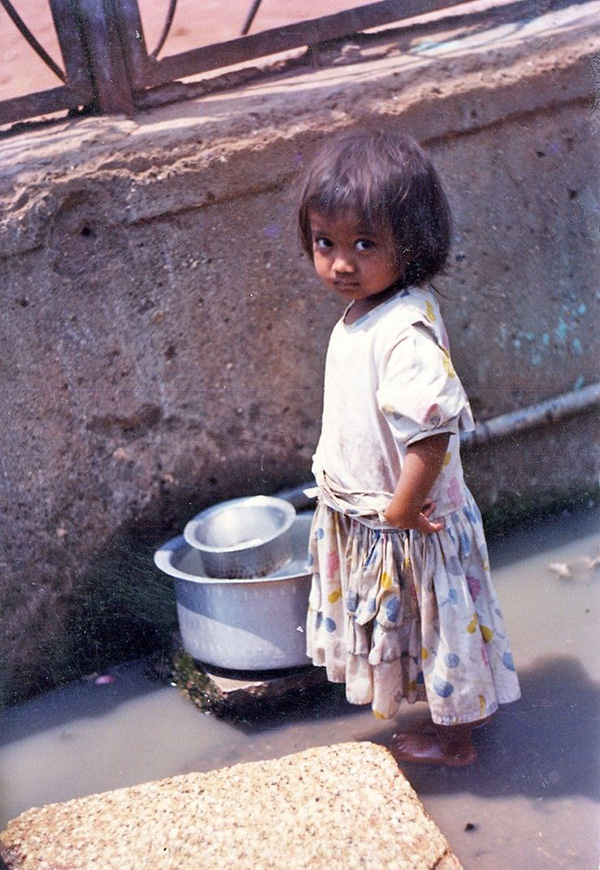

In the everyday world, hunger is 5-year-old Meena, who was reduced to begging for scraps from strangers and eating sewage-soaked dirt off the streets of Mumbai, India. Not long after her haunted image was photographed, she went into a coma and died.

It is not only an issue in parts of the world where lack is as clearly obvious, however. People also suffer from hunger in places like Liverpool, England, where one young boy chewed wallpaper at night, not wanting to tell his mother how hungry he was because he knew that she didn’t have any money for supper.

Concerted attempts to eradicate hunger are not new. Though he rallied the collective effort to put a man on the moon in the 1960s, President John F. Kennedy was less successful in achieving another ambitious goal he voiced.

“We have the ability, as members of the human race, we have the means, we have the capacity to eliminate hunger from the face of the earth in our lifetime,” he said. “We need only the will.”

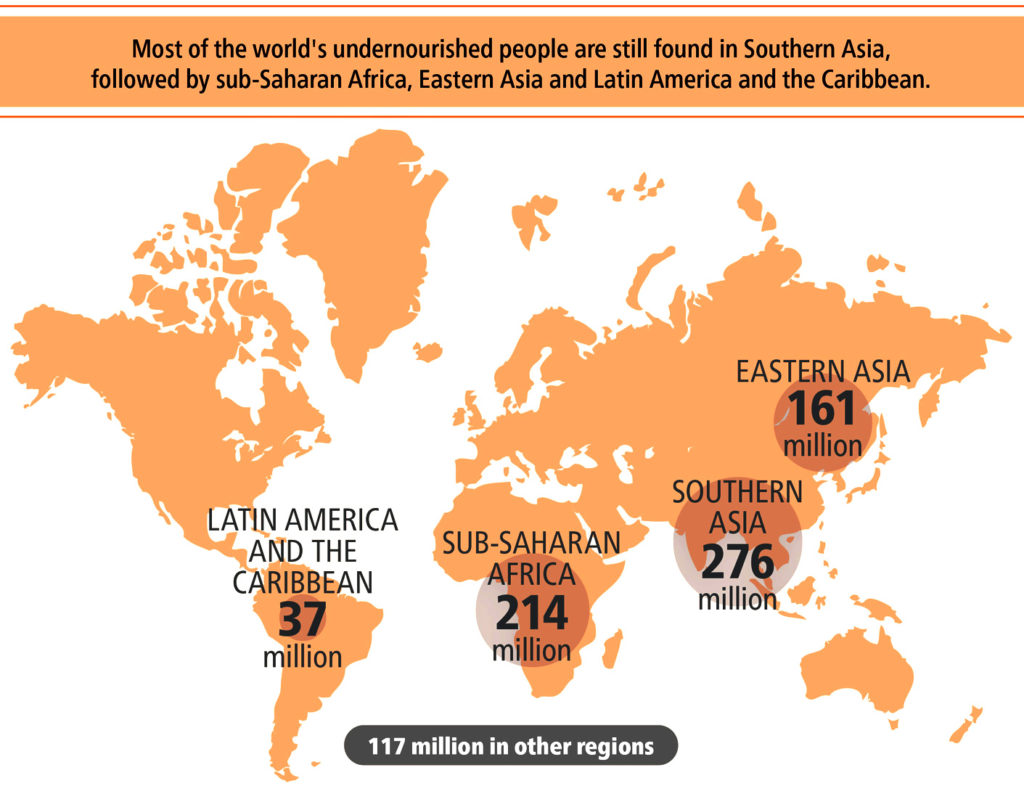

Despite best efforts, from governments to the grassroots, it is not a problem that is going away. Worldwide, hunger increased in 2018 for the third successive year. According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, more than 820 million people did not get enough to eat that year.

The largest concentration of undernourished people is in Asia, especially South Asia, with the region accounting for two-thirds of all the malnourished children in the world. In India, nearly 200 million people are undernourished. The country was ranked 103rd of 119 in the 2018 Global Hunger Index.

According to the UN report, however, Africa “has the highest rates of hunger in the world and [these] are continuing to slowly but steadily rise in almost all subregions.” Indeed, more than a quarter of Africa’s population was classified as food-insecure in 2016, more than four times the rate of any other region. The Global Hunger Index includes six African nations among the ten hungriest worldwide: the Central African Republic, Chad, Madagascar, Zambia, Liberia and Zimbabwe.

“We have the ability, as members of the human race, we have the means, we have the capacity to eliminate hunger from the face of the earth in our lifetime, we need only the will.”

President John F. Kennedy

World Food Congress, June 4, 1963

One small indicator of the seriousness of hunger is that it gets not one but two annual days of international attention. This year’s World Hunger Day (May 28) will focus on “sustainability.” Organized by The Hunger Project, it will emphasize how long-term solutions must address issues interwoven with hunger, such as political instability, the environment and gender inequality. The U.N.’s World Food Day is to be observed October 16, marking the founding of the body’s food and agriculture organization.

World Hunger’s Ugly Truths Revealed

Each year, Gospel for Asia (GFA) workers recognize the U.N. event with a host of special feeding programs. They take food packages to local communities in need—including homeless people who beg by railway and bus stations—and prepare meals for the residents of leprosy colonies who are ostracized and unable to find work.

As Gospel for Asia (GFA) workers provide simple, nutritious food—such as bread, eggs, and bananas, pulse curry and vegetables—they extend a lifeline to people like Lalita. At 32 she had been living by the footpath near a railway station when some of Gospel for Asia (GFA)-supported Sisters of Compassion arrived with food.

“I lost my husband six years ago, after which my family abandoned me, as I am blind,” she told the visitors. “Now, I cannot do any work. Today I am happy that I received this food packet.”

Hunger is ugly on many levels, not least because many of its root causes are human action and inaction—wars, corruption, and environmental mismanagement. Three additional realities make it even more difficult to swallow:

- There is enough food in the world to go around.

- A lot of good food just gets thrown away, some merely because it doesn’t look picture-perfect.

- While millions go hungry because they can’t afford to eat, others spend large amounts of money following fad diets.

Pope Francis called out some of these wrongs in a 2019 World Food Day message: “It is a cruel, unjust and paradoxical reality that, today, there is food for everyone, and yet not everyone has access to it, and that in some areas of the world food is wasted, discarded and consumed in excess, or destined for other purposes than nutrition.”

Improvements in global food production mean that the world produces a harvest big enough to feed everyone on the planet one-and-a-half times over. Yet fully a third of all the food that is produced goes to waste—discarded in production, lost somewhere along the farm-to-table route, or thrown away by end-consumers: restaurants, institutions like hospitals, and families. It has been reckoned that, globally, around $1 trillion worth of food is lost or wasted each year.

Losses before food gets to the consumer are highest in Central and South Asia, reflecting the bigger challenges in the supply chain there. However, North America is high in the overall waste league—some 133 billion pounds each year.

And that’s just considering the immediate value of the food. The wider cost is “a major squandering of resources, including water, land, energy, labor and capital.”

The War on Waste

Thankfully, efforts are being made to cut the terrible waste. The World Union of Wholesale Markets, a nonprofit group representing more than 150 wholesale markets around the world, has committed to new collaboration with the U.N.-FAO to improve distribution. Only a fraction of the food business world may be involved in the initiative, but it’s a start.

Meanwhile, big businesses are recognizing the need to be better stewards. At a special gathering on reducing loss hosted by the International Food Policy Institute, Kroger executive Denise Osterhues spoke of her company’s steps in that area. The senior director for corporate affairs told how Kroger had begun marking down red-bagged produce when it neared expiration date, introduced a “Pickuliar Picks” line of imperfect produce, and developed clearer date labeling to help consumers make the most of their food purchases.

Like a growing number of other food retailers and servers, Kroger also donates surplus and past-date supplies to charitable organizations for redistribution. It gave away 90 million pounds of produce in 2018.

Pope Francis, World Food Day 2019

Many different charitable organizations are eager to make use of produce that doesn’t get sold for one reason or another. In 2018, the 800 members of the Global FoodBanking Network alone distributed around half a million tons of food and grocery products.

At a plant in Sultana, in the heart of California’s breadbasket San Joaquin Valley, Gleanings for the Hungry recycles bruised and misshapen fruits and vegetables from growers in the area for shipping around the world. This ministry of Youth With a Mission (YWAM) takes its name from the directive in Leviticus 19 that the Israelites should not reap to the edges of their field, but leave the “gleanings” for the poor to gather up. For the last 40 years, Gleanings for the Hungry has processed and distributed millions of pounds of produce through partner organizations.

In Singapore, Pei Shan co-founded Ugly Food to make use of the produce that shoppers ignore because it doesn’t look nice enough. Her company turns the rejected items into healthy juices, ice cream bars, and fruit teas.

“Ultimately, we want our business to create a conversation about ‘cosmetic filtering’ and to help others rethink what they consider as waste,” she says.

Feeding India’s Magic Wheels program is a fleet of trucks that collects unused food from canteens, wedding receptions, and other events for redistribution. The vehicles are equipped with temperature-controlled insulated boxes to keep the food fresh, and donors are given a liability release form to protect them. Feeding India has also set up Happy Fridges in residential and public spaces in 25 cities. The refrigerators are stocked free by donors, and available for anyone to come and take what they want, free of charge.

Launched in Delhi in 2014, the Robin Hood Army, a zero-funds organization that relies on volunteers to collect and distribute leftover food from restaurants and other businesses, has since served more than 26.5 million meals in more than 150 cities across a dozen countries.

How Hunger Harms the Human Body

Nutrition is about more than just having enough to eat, though. It’s having the right things to eat. Sometimes a body may be seemingly well-fed, but actually starving of the nutrients it really needs.

That is why, though it seems almost contradictory, there has been an alarming rise in obesity, including in low-income countries in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South and East Asia. A U.N. study in Latin America and the Caribbean found that the percentage of people there with obesity had tripled since 1975, while hunger increased 11 percent in the last four years.

That is why, though it seems almost contradictory, there has been an alarming rise in obesity, including in low-income countries in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South and East Asia. A U.N. study in Latin America and the Caribbean found that the percentage of people there with obesity had tripled since 1975, while hunger increased 11 percent in the last four years.

As a complex machine, the human body needs high-grade fuel to run well. Without it, systems start to break down. In parts of the world where food is scarce or of poor quality, the lack of vital vitamins and minerals has a serious impact.

Insufficient iron, a condition often made worse by malaria and other infectious diseases, makes pregnancy more risky and impairs physical and cognitive development. Lack of vitamin A can lower a person’s resistance to disease, impair growth in children and cause blindness. Lack of iodine is one of the major causes of reduced cognitive development in children.

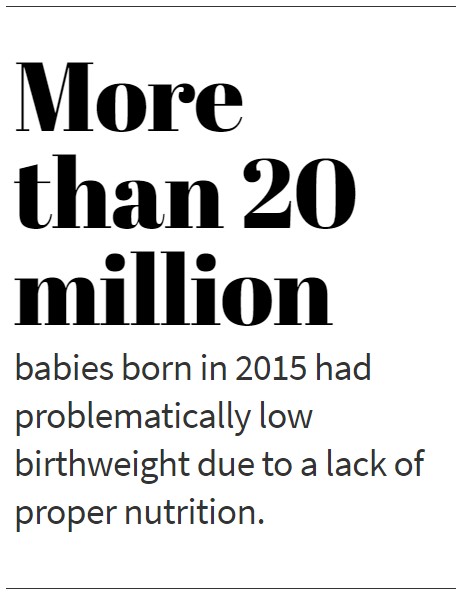

All this lack of proper nutrition poses an especially severe threat to pregnant women and newborn babies: One in seven of 2015’s live deliveries—more than 20 million babies—had a problematically low birthweight.

Hunger is inextricably linked to poverty, which in turn can’t be separated from war, political unrest, and prejudice.

Millions starve because of others’ actions and inactions,

without even taking into account natural disasters.

A good diet is especially crucial in the first three years, when young brains and bodies are developing. Ironically, malnutrition is linked to a higher risk of being overweight and chronic diseases like diabetes in later life.

An article by Lauren Weber graphically illustrated the importance of a good diet’s importance. A photograph featured in the article showed a dramatic difference between two five-year-olds born on the same day in Madagascar: Miranto, a good student, stood more than a head taller than Sitraka, who was unable to attend school because he hadn’t yet learned to speak properly and had trouble being still for any length of time. The difference? Their diet.

Sitraka was a victim of “stunting,” low height for age because of chronic nutrient deficiency. Like him, “most chronically malnourished children are shorter than their healthier peers,” she states.

In 2017, the UN found almost 151 million children under age 5 were too short for their age due to malnutrition. Africa and Asia accounted for 39 percent and 55 percent of all stunted children, respectively. Nearly 38 percent of children under 5 in India were found to be stunted in 2018, accounting for a third of the world’s total. The countries with the next-highest numbers were Nigeria and Pakistan.

Such children’s immune systems are weaker, “leaving them more susceptible to repeated infections. And their brains do not develop fully, leading to lower IQs and a decrease in lifetime productivity” said Weber.

“Wasting,” meanwhile, is evidenced by low body weight for age, with the associated reduced muscle mass leaving children at greater risk of death from what might otherwise be minor infections. In 2017, one in ten children in Asia was underweight for their age, compared to just one in 100 in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Hunger’s Hidden Costs

The high cost of hunger might be seen better by evaluating its absence.

“In adulthood, per capita income of individuals who were not stunted at two years is higher compared to individuals who were stunted at two years,” said the U.N. “This increase comes about through the impact of improved nutrition on income through higher schooling and better cognitive skills. In fact, a reduction in global levels of stunting by 20 percent would represent a rise in income of 11 percent.”

Hunger doesn’t just endanger people’s physical and intellectual development. It can damage their souls as well as their organs.

After visiting Zimbabwe, a country ravaged by drought and a sluggish economy, Hilal Elver, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, noted some other effects of food scarcity.

“The most vulnerable segments of society, including the elderly, children and women, are forced to rely upon coping mechanisms such as, school dropout, early marriage, and sex trade to obtain food, behavioral patterns that often are accompanied by domestic violence,” she said. “This kind of struggle for subsistence affects their physical well-being and self-respect. It creates behavior and conditions that violate their most fundamental human rights.”

In common with other big social issues, it’s women and children who are often worst affected by hunger. Young women need iron-rich food to replenish what’s lost during menstruation, or they will face anemia, which can lead to heightened incidence of maternal deaths and stillbirths. A World Food Programme (WFP) study found 15- to 19-year-old girls in one part of Uganda had anemia rates two to three times higher than the national average.

The WFP report urged making greater efforts to keep adolescent girls in school and provide them with nutritious diets. A separate study by the organization found multiple benefits from school feeding programs in Indonesia. Enrollment, attendance, and understanding went up, while drop-out rates fell. The benefits went beyond the individual students and their futures, however.

Free school meals made limited household money available for other needs, which reduced the pressure on keeping kids away from school to help around the home or earn income. The study concluded that for every dollar invested in the feeding program there would be a five-fold return to the economy over the lifetime of each beneficiary.

As with all big social issues, hunger issues are complex. Hunger is inextricably linked to poverty, which in turn can’t be separated from war, political unrest, and prejudice. Millions starve because of others’ actions and inactions, without even taking into account natural disasters.

Malnutrition isn’t just a result of not having enough to eat, or even not having enough of the right things to eat. World Hunger notes that in many parts of Asia, “poor and insufficient sanitation and hygiene practices can increase the spread of disease and infection.” Two central sanitation issues contribute to up to half the cases of child malnourishment: the lack of access to clean water, and the presence of open defecation, which is still a problem in many parts of India. The elimination of the practice has been sought through a large-scale push of education and construction of community toilets undertaken by India’s government and non-profit groups such as Gospel for Asia (GFA).

In Ethiopia, a focus on ending open defecation helped to drastically improve nutrition levels and cut child stunting almost in half between 2000 and 2014, though the reduced 40 percent level remains “unacceptably high.”

The downward spiral of inadequate diet and poor sanitation and hygiene has been spotlighted in a United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund report: “Diarrhea or infectious disease can cause loss of micronutrients or inhibit consumption of sufficient nutritional foods, weakening an individual to become more susceptible to severe illness, and thus exacerbating the micronutrient deficiency.”

Hunger Close to Home

If hunger is obvious across great swaths of Africa and Asia, it is not so evident in other parts of the world. But that does not mean it is not an issue. Hans Konrad Biesalski, a German physician and professor of chemistry and nutrition, has detailed the challenge of “hidden hunger” in a similarly titled book.

He refers to micronutrient malnutrition, which affects a third of the world’s population. Even if someone’s stomach isn’t entirely empty, it may not be filled with the vitamins and minerals their body needs. Citing a four-fold increase in cases of rickets in England over a 15-year period, he warns that micronutrient inadequacies “are to be found in the developed world as well as in the developing world, and their current European rate of growth in the developed world gives cause for concern.”

According to the U.N., more than 2 billion people, the majority in low- and middle-income countries, do not have access to enough safe and nutritious food. It is not exclusively a problem of poorer nations: One in 12 of the population of North America does not get to eat enough regularly.

Many people go hungry in the United States, though typically more episodically than continually, as in other parts of the world. Just over one in ten American households—almost 40 million people, 11 million of them children—were “food insecure” at some stage during 2018. The good news is that figure is down from the Great Recession rates of a decade ago.

Rates of need varied widely from less than eight percent in New Hampshire to almost 17 percent in New Mexico. Overall, food insecurity was higher in cities than in rural communities, with the suburbs faring best.

From its research, Feeding America finds children in the U.S. more likely to face hunger than the rest of the population, ranging from one in ten in North Dakota to one in four in New Mexico. The organization notes that the health, social, and behavioral problems hungry children are at risk from are exacerbated during school holidays, when feeding programs are suspended.

Good News in Word and Deed

While GFA’s field partners join in the awareness-raising focus of World Hunger Day and World Food Day, they are more quietly involved in tackling hunger year-round. Food is an integral part of the 500-plus Bridge of Hope centers run in slums and villages across South Asia. The free education program, which is currently being offered to around 70,000 enrolled children, is a fundamental part of helping improve their futures, and lunch is as important as the lessons.

For students like brother and sister Panav and Kajiri, the nutritious curry and rice they served at Bridge of Hope is an important supplement to the basic food they get at home: bread and milk for breakfast, with fried vegetables, eggs, and chapatis for supper.

Some question faith-based organizations’ involvement in humanitarian efforts like feeding the hungry, despite Jesus’ clear example of caring for the poor in practical ways, because they suspect mixed motives among givers or receivers, or both. They talk of so-called “rice Christians,” who pay lip service to belief for the benefits they get.

For K.P. Yohannan, it’s a false dichotomy. “The huge battles we face against hunger, poverty and suffering in Asia and around the world are in part spiritual, not simply physical or social as secularists would have us believe,” he says. “We cannot separate the visible and the invisible in this battle.”

Sometimes providing food for today is all that can be done, but GFA’s field partners look for ways to provide food for tomorrow and the day after. Their work follows the old adage about giving someone a fish, to feed them once, or teaching them to fish, so they can continue to feed themselves.

GFA’s field partners provide fishing nets and other income-generating supplies such as sewing machines, livestock and rickshaws through Christmas gift distribution programs. Palan stands among thousands of people who have received such gifts. Since Palan had no land of his own to work, his income depended on the fish he could catch, but he had only one poor quality net. The one he received through the Gospel for Asia (GFA) supported gift distribution means he can now meet his needs. In 2018, Gospel for Asia (GFA) workers presented income-generating and life-improving Christmas gifts to almost a quarter of a million people like Palan.

It is easy to get overwhelmed by the scale of a problem, believing that one person’s efforts will not make much of a difference. But Jesus’s example of addressing hunger offers one of the greatest examples of how giving just a little can make a big impact.

After a long day listening to Him teach, the crowd of thousands was hungry. When Jesus told His disciples to feed them, they couldn’t see how. They only had the lunch a small boy offered: five barley loaves and two fish. Yet God multiplied that to meet everyone’s needs.

In the same way, we should not focus on what we think can’t be achieved. We should instead give and do what we can with the faith and expectation that God will take and use it in a way that exceeds what seems possible. What are practical ways to do that?

Be more intentional about reducing the amount of food that gets wasted in your home, to help make a dent in the squandering supply chain.

Support local organizations that redistribute surplus produce to those in need. You don’t even need to leave home to do that: the annual National Association of Letter Carriers’ Stamp Out Hunger National Food Drive sees mailmen and -women collecting donations of non-perishable foods on their rounds on the second Saturday in May.

Each time you dine out, buy someone else a meal by donating to Gospel for Asia (GFA) or some other organization feeding the hungry.

These small steps may not seem like much, but they certainly count in God’s sight. When Jesus told His followers they will be rewarded for having fed Him when He was hungry, He said that some would be perplexed.

“Lord, when did we see You hungry and feed You?” they will ask. The King will respond, “Assuredly, I say to you, inasmuch as you did it to one of the least of these My brethren, you did it to Me” (Matthew 25: 37, 40).

Give Food, Aid to Victims of Hunger & Starvation

Read more news on World Hunger and Gospel for Asia on MissionsBox News.

This Special Report originally appeared on gfa.org.

Read another Special Report from Gospel for Asia on Poverty: Public Enemy #1 – Eliminating Extreme Poverty Worldwide is Possible, But Not Inevitable.

Learn more by reading this special report from Gospel for Asia: Solutions to Poverty-Line Problems of the Poor & Impoverished — Education’s Impact on Extreme Poverty Eradication.