Gospel for Asia (GFA World) Special Report on Slavery & Human Trafficking

![]() Written By Palmer Holt of InChrist Communications

Written By Palmer Holt of InChrist Communications

Around 10 million people are currently behind bars somewhere in the world. Some have yet to face trial, a few have been wrongly convicted, but most are prisoners for a crime they have committed.

Meanwhile, four times as many people are being held against their will because of a crime committed against them—they are part of the global slave population estimated to be more than 40 million.

That number is higher than the entire population of Canada. Many of these victims are literally kept under lock and key, while others are effectively imprisoned by coercion, manipulation and extortion.

Slavery may long have been officially outlawed, but difficult though it may be to believe, numerically there are more slaves today than at any time in history.

Among them:

- Twin brothers, Aimamo and Ibrahim, who at age 16 left grinding poverty in their native Gambia for what they hoped would be a better new life in Libya.

Instead of well-paying jobs, they found themselves enduring beatings and threats as they labored on a farm alongside scores of other sub-Saharan Africans, locked in at night to keep them from escaping.

Instead of well-paying jobs, they found themselves enduring beatings and threats as they labored on a farm alongside scores of other sub-Saharan Africans, locked in at night to keep them from escaping.- “A,” who was sent by her desperate mother to live with another family in Asia as a servant after the death of her father.

- Forced to work from morning to night cleaning dishes and washing clothes, the small girl was beaten and slapped when she didn’t keep up. And when she fell asleep one night while massaging the legs of her “owner,” the woman smeared chili powder into her eyes as punishment.

- “K,” who was sold at age 5 by family friends and then taken to truck stops along route 80, one of the busiest interstate highways in the United States.

There, anesthetized by drugs and alcohol, this little girl would be forced to knock on the doors of the trucks and sell herself to the drivers.

Since 2011, almost 90 million people have experienced some form of modern slavery for periods of time ranging from a few days to several years.

Since 2011, almost 90 million people have experienced some form of modern slavery for periods of time ranging from a few days to several years.

Total profits from this trade in slave labor are dwarfed only by sales of illegal drugs and illicit arms.

“Every country in the world is affected by human trafficking,” says the United Nations, “whether as a country of origin, transit, or destination for victims.”

So concerning is the issue that it is spotlighted by not one but two of the UN’s annual international awareness days.

The World Day Against Child Labor (June 12) highlights the plight of nearly 170 million children worldwide who have to work—half of them in “hazardous” situations—and whose number includes those in bonded labor. Though the number of working children has dropped significantly since the turn of the millennium, that pace of decline has “slowed considerably” in the past few years, says the International Labor Organization.

Meanwhile, children comprise a third of all victims of human trafficking, which is the focus of the World Day against Trafficking in Persons (July 30).

Money from Misery

That human trafficking relates to two UN days of awareness also hints at the complexity of the issue. Because the particularly harrowing nature of sex trafficking means it garners a lot of headlines, many people assume this is the main area of human trafficking.

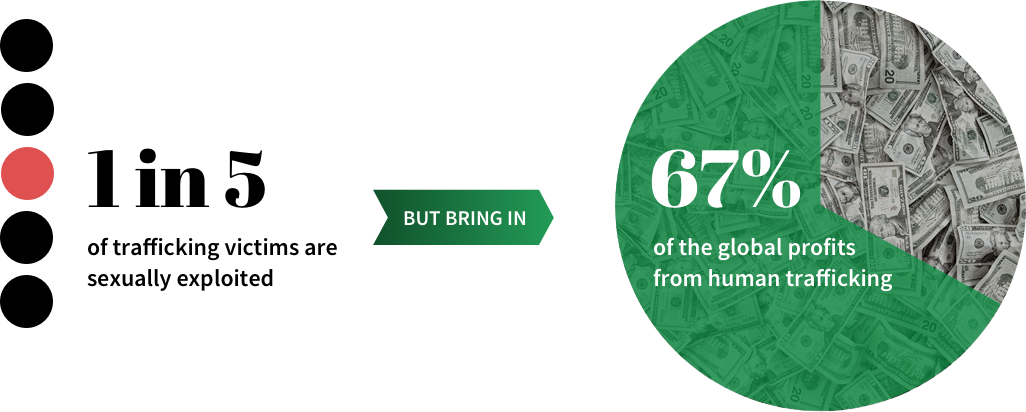

However, research tells another story: Of the 25 million people ensnared in forced labor in 2016, only 5 million were involved in sexual exploitation.

Sex trafficking doesn’t only generate more headlines than other forms, though; it also generates a lot more money.

One in five trafficking victims may be sexually exploited, but they bring in two-thirds of the total global trafficking profits.

A typical woman forced into prostitution makes around $100,000 a year of profit for those who control her, six times the average profit of other forced workers.

Human Rights First says that studies have shown that sexual exploitation can yield a return on investment ranging from 100 percent to 1,000 percent, while an enslaved laborer in less profitable markets—such as agricultural work—can generate something over 50 percent profit.

Such numbers underscore how human trafficking is really big business. As with so many of the world’s major problems, the causes are complex. Politics and prejudice, commerce and corruption, disasters and discrimination are all part of the roots of this diseased tree.

“Vulnerability to modern slavery is affected by a complex interaction of factors related to the presence or absence of protection and respect for rights; physical safety and security; access to the necessities of life such as food, water and health care; and patterns of migration, displacement and conflict,” say those behind the sobering 40 million statistic.

Meanwhile, Anti-Slavery International (ASI) lists “strict hierarchical social structures and caste systems; poverty; discrimination against women and girls and lack of respect for children’s rights and development needs” among the fertilizers.

However, one thing distinguishes human trafficking from many other key global issues.

“This is a human condition,” says Australian businessman and anti-slavery campaigner Andrew Forrest. “This isn’t AIDS or malaria or something which is thrust upon us by nature. This is the choice of man, so the choice of man can stop it.”

There are widespread efforts being made to do that, from those advocating for changes in the law to those pushing for businesses to take more responsibility for the shadow side of globalization. Others work with authorities to free people from brothels and brick factories or, like many Gospel for Asia (GFA)-supported workers, care for and help to rehabilitate the victims left with physical and emotional scars.

Those shocked by the scale of slavery in the 21st century, imagining it had effectively been abolished in the 1800s, may be equally surprised by its many forms. They range from sex trafficking and forced marriage—some 15 million people in 2016, many of them young girls—to forced labor and bonded labor.

The latter is especially common in Asia, where exorbitant interest rates by lenders can lock generations of families into working to pay off what began as a small debt—likely for an essential such as food or medicine—that keeps mushrooming.

“This isn’t AIDS or malaria or something which is thrust upon us by nature. This is the choice of man, so the choice of man can stop it.”

“Modern slavery takes many forms and is known by many names,” says the Freedom Fund.

“Today’s slaves are trapped in fishing fleets and sweatshops, in mines and brothels, and in the fields and plantations of countries across the world. It can be called human trafficking, forced labor, slavery, or it can refer to the slavery-like practices that include debt bondage, forced or servile marriage, and the sale or exploitation of children.”

According to Free the Slaves, today’s trade has two chief characteristics: It’s cheap, and it’s disposable.

“Slaves today are cheaper than ever,” says the group. “In 1850, an average slave in the American South cost the equivalent of $40,000 in today’s money. Today a slave costs about $90 on average worldwide.”

Human trafficking may be a global disease, but it is more virulent in certain parts of the world, where poverty and social inequality more readily enable it to thrive. The 2016 Global Slavery Index (GSI) found that just five countries accounted for almost 60 percent of the global slave population.

Cashing In on Chaos

Like a virus, human trafficking continues to mutate. Women have long been considered to be the main victims, and that is certainly true in the sex trade, where they comprise 99 percent of those used and abused.

However, GRETA (Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings) found that, in some countries, labor trafficking has emerged as “the predominant form.” And while there are “considerable variations in the number and proportion of labour trafficking victims amongst evaluated countries, all countries indicated an upward trend of labour exploitation over the years.”

As the numbers of those trafficked for forced labor have increased over the last decade, so has the number of trafficked men, who can be subject to particularly brutal treatment. Survivors of forced labor in the Thai fishing industry have told of being made to take amphetamines to enable them to work long hours and of being dragged through the water with a rope around their neck for complaining.

Those who tried to escape were executed and their bodies thrown overboard.

Trafficking has also grown and morphed in the wake of the refugee crises in Europe and parts of Africa and Asia.

“Refugees and unaccompanied children are some of the most vulnerable targets of labor and sex traffickers,” warns the UN.

Mass movements of people in times of great upheaval leave many vulnerable to being taken advantage of and provide opportunities for traffickers to move even more freely.

“In the chaos of conflict and violence, a perfect storm of lawlessness, slavery, and environmental destruction can occur—driving the vulnerable into slave-based work that feeds into global supply chains and the things we buy and use in our daily lives,” say the GSI publishers.

“Modern forms of slavery prosper in these environments of conflict, corruption, displacement, discrimination and inequality,” they add. “Given this, it is critical that national and international responses to humanitarian emergencies and mass migration take account of the very real risks of modern slavery on highly vulnerable migrant and refugee populations.”

“In 1850, an average slave in the American South cost the equivalent of $40,000 in today’s money. Today a slave costs about $90 on average worldwide.”

If selling trafficked bodies is grievous, then selling trafficked body parts is gruesome, but it happens. As many as 7,000 kidneys are illegally obtained by traffickers every year as demand outstrips the supply of organs legally available for transplant, says Fight Slavery Now. This organization references a refugee camp given the nickname Kidneyvakkam, or Kidneyville, because so many women there had sold their kidneys.

“A black market thrives as well in the trade of bones, blood and other body tissues,” says the organization.

A particularly disturbing aspect of human trafficking is how often perpetrators take advantage of people’s hopes and desires to prosper. Many migrant workers are lured from their home country by promises of a new life—only to find a darker reality.

Maya was 22 when she fled the fighting in her native Syria, destined for Lebanon where she had been promised a job working in a factory. But upon her arrival, she found herself forced into prostitution with many others, enduring “severe physical and psychological violence,” before finally being rescued.

It’s all too common for migrants trying to get into a new country without the proper papers to be tricked by those claiming to help them, but they are not the only ones to find they have been duped.

Hundreds of welders and pipe-fitters who were recruited to help fix oil rigs damaged by Hurricane Katrina arrived in the United States legally—some having paid as much as $25,000 in recruiting fees for the opportunity.

But upon arrival, things were very different. They found themselves in an isolated, barb-wired compound with armed guards, where they were forced to live in crowded shipping containers—as many as 24 men in one unit—and for which they were charged $1,000 monthly rent. Underfed, they had to work round the clock for virtually nothing by the time a slew of deductions was made from their wages.

Traffickers lure their victims with false promises and then keep them imprisoned, sometimes literally and sometimes by threats of violence. When victims have been taken to a different country, they can be reluctant to go to the authorities for help for fear of being deported. As a result, traffickers may not keep their victims in locked rooms but “hide them in plain sight,” knowing they will not try to escape.

That “plain sight” may include the local hand car wash. In the U.K. there is concern that “endemic exploitation” occurs at the 20,000 such operations in the country.

“The truth is that ordinary people everywhere in the world … unwittingly come into contact with victims of modern slavery every day,” says Forrest. “We might walk past a little girl trapped in a forced marriage, a hotel cleaner that has had her passport confiscated, or touch this crime through the clothes and products made through illegal forced labor that we use every day.”

Traffickers will also play on victims’ vulnerabilities. When Gowri, who was tricked into bonded labor, tried to leave the brick kiln where she was being held, the owner attacked her children and then her.

Children at Risk

The widespread exploitation of children isn’t limited to working in fields and factories. Cruelly, they also may be enslaved in a place that is supposed to be a haven.

Many children are at risk of being exploited in orphanages, home to some 8 million children worldwide—and four out of five of whom are not actually without a parent or parents.

They may have ended up in care because their desperately poor parents thought they would be better cared for by others.

But that does not always turn out to be the case. Some orphanage operators have deliberately withheld food and proper living environments to keep the youngsters looking malnourished “to attract more sympathy and therefore more money via donations.”

So-called “paper orphans” are said to be used as moneymakers in countries like Nepal, Cambodia, Ghana, Uganda, Guatemala and Haiti, tapping into the growing “voluntourism” market of the West, combining travel with a dash of doing good.

And there is “a strong but largely unrecognized connection between institutionalization and trafficking.”

It is bad enough that many of those who volunteer at orphanages don’t have any credentials and that the high turnover of visiting caregivers is believed to lead to attachment disorders among the children. Yet even more alarming is that orphanages can be a rich target for pedophiles.

“Modern forms of slavery prosper in these environments of conflict, corruption, displacement, discrimination and inequality.”

For being such a large criminal operation, human trafficking sees limited disciplinary action. According to the U.S. State Department’s 2017 Trafficking in Persons report, there were only 14,897 prosecutions and 9,071 convictions for trafficking globally the previous year. In South and Central Asia, the number of prosecutions rose between 2010 and 2016—but only from 1,500 (with 1,000 convictions) to 6,250 (2,200 convictions).

Partly this is because of limited manpower and other resources. International Justice Mission (IJM) notes that many police departments in Asia “often lack the most basic office supplies—paper, folders, functional phones, copiers and computers—let alone forensics evidence kits, DNA testing equipment, and cameras necessary to do their job.”

But there is a darker reason for the widespread impunity with which many human traffickers work: corruption. As the UN has observed, “most poor people don’t live under the shelter of the law, but far from the law’s protection.”

IJM founder and CEO Gary Haugen says the last half-century has seen “the almost total collapse of functioning criminal justice systems in the developing world.”

When cases are investigated, it’s not uncommon for them to be settled out of court in parts of Asia because the victims’ need for money trumps justice, allowing the offenders to continue their trade.

Champions of Change

Clearly, governments have a major role to play in ending slavery, and leaders are taking steps in places like India, where tougher anti-trafficking laws have been pursued.

In 2016, child rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi launched the global “100 million for 100 million” campaign, which challenges the world’s children living in better circumstances to speak up on behalf of disadvantaged children. Then-President Pranab Mukherjee’s support of the campaign has been acknowledged as part of a “historic move towards ending child slavery in India.”

Of 161 countries profiled in the Global Slavery Index, 150 governments provide some kind of services for victims, 124 have criminalized human trafficking, and 96 have national action plans to do something about it.

Perhaps fittingly, the strongest government lead has been taken in England, where William Wilberforce and other campaigners led the fight to end the slave trade of the 19th century.

Naming modern slavery the “greatest human rights issue of our time,” the U.K. government appointed a slavery commissioner to lead its efforts and became the first to develop a modern slavery initiative in 2014. The following year it passed the Modern Slavery Act, requiring business action. It means that U.K.-based companies with total annual global incomes of more than $50 million have to publish transparency statements that detail what they are doing to ensure that the supply chains they are part of do not use slave labor.

Global trade is so complex these days that “it is near certain that slavery can be found in a supply chain of every single company, and it is near impossible to guarantee a slavery-free product,” Anti-Slavery International acknowledges.

Indeed, the U.K. slavery commissioner estimates that 16 million of the world’s enslaved people are somehow working for companies.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Labor has a list of almost 150 goods from 75 countries believed to be produced by child or forced labor. It includes matches and footwear from Bangladesh, bananas from Belize, fireworks from China and soccer balls from India.

Many migrant workers are lured from their home country by promises of a new life—only to find a darker reality.

The complexity doesn’t give businesses a pass, however.

“Our homes and our businesses carry the imprint of modern slavery,” says Forrest, the billionaire founder of Walk Free Foundation. “As business leaders, it is our responsibility not to turn a blind eye, or to pretend that we are unaware, or believe that the issue is too complex to deal with.”

An example of effective action is IKEA’s IWAY code, in which the furniture giant sets out standards for its suppliers, including the right to make unannounced site visits to direct partners and contractors. In the U.K., there has been a move among hotel operators to start a network to tackle human trafficking in the industry.

GFA’s Work Among Victims of Slavery

Among the many unnamed helpers are scores of Gospel for Asia (GFA)-supported workers. They care for women and girls ensnared in the red-light districts of some of Asia’s major cities, and they run Bridge of Hope (BOH) centers that provide schooling and medical care, aiming to help children escape forced labor and provide them with a better future.

One who was helped is Nadish. He was held as a slave for two years from age 9. During his years in slavery, he was locked overnight in a room near the animals whose waste he had to clean up and was given very little food. Though he eventually managed to escape and find his way back home, he continued to struggle with the effects of his imprisonment and ill-treatment. Throughout his recovery, Nadish had his Bridge of Hope teachers to comfort, pray for and love him.

“A,” who was mentioned earlier in this report, was eventually rescued from her enforced laborer by authorities. She has been healing from her ordeal at a home for abandoned and at-risk children where Gospel for Asia (GFA)-supported workers serve. No longer made to work, “A” can be a child again. Playing with children her age and learning songs and dances with other girls, she enjoys being able to attend the home.

“I like this place so much; I like all these didis (older sisters),” “A” says. “They work hard for me and for all of us. I like this place and I don’t [want] to leave this place and go to any other place or orphanage because of the love and care that we get here.”

Through GFA’s ministry, children and their families don’t only receive practical help; they also hear about God’s love for them.

“It’s amazing how the love of Christ brings hope to the poorest of society and fills the hearts of these children with joy,” says Dr. K.P. Yohannan, founder and director of Gospel for Asia (GFA).

Gospel for Asia (GFA)-supported work with children like Nadish and “A” is a critical part of the anti-slavery effort. Prevention is a major part of the battle. Giving children and families hope for a better future through education offers them something to turn to other than child marriage or bonded labor, and children who have people carefully watching out for them—like Bridge of Hope teachers—and who will be missed if they vanish are less vulnerable to trafficking. The daily meal, medical care and school supplies provided for students ease parents’ financial burden, enabling them to focus their hard-earned income on other crucial family needs.

While slavery is a global problem that’s difficult to eradicate, there is still hope. As Forrest said, “This is the choice of man, so the choice of man can stop it.”

To read more posts on Missions Box on this pertinent issue of the ongoing global problem of slavery, go here.

For more information about this, click here.