Gospel for Asia (GFA World) Special Report on Mosquito Netting and Malaria Prevention Combat a Parasitic Genius

![]() Written By Ken Walker of InChrist Communications

Written By Ken Walker of InChrist Communications

Fighting Malaria. Though eradicated in many developed nations, malaria still claims thousands of lives around the world. One victim who survived this mosquito-borne disease compared its chills to “lying down between two blocks of ice.”

Each year, more than 400,000 people don’t survive those terrifying shudders.

As part of its long-term goal to eradicate malaria, this year the World Health Organization (WHO) is launching the first field test of a vaccine in real-world settings. Known as RTS,S, or Mosquirix™, the United Nations agency says this is the first vaccine shown to provide partial protection against malaria in young children by acting against the deadliest parasite globally. It will be made available to select residents of three countries in Africa, the continent linked to the highest number of cases. In addition to combating it, the organization hopes to train a spotlight on the need for dramatically increased funding for fighting malaria.

“Progress in the global malaria response has unquestionably stalled,” said Dr. Pedro Alonso, director of WHO’s Global Malaria Program, in a letter last December.

“Clearly, to get the response back on track, increased funding is urgently needed from international donors and endemic countries. Critical gaps in access to tools that prevent, diagnose and treat malaria must be found and filled.”

To get an idea of the obstacles presented by malaria, consider the toll during 2016. Worldwide, there were 216 million cases, an increase of 5 million over the previous year. The death toll of 445,000 nearly matched that of 2015.

Although $2.7 billion was invested in the fighting malaria in 2016, WHO estimates a minimum of $6.5 billion will be needed annually by 2020.

A life-threatening disease, malaria is caused by parasites transmitted to people through bites of infected female mosquitoes, known as anopheles. In people lacking immunity—especially pregnant mothers and young children—symptoms appear 10 to 15 days after the bite. Fever, headache, chills and vomiting are among the symptoms.

Severe cases in children can include severe anemia and respiratory distress, while in adults, the disease can affect multiple organs. Without treatment within 24 hours, certain kinds of malaria can cause death.

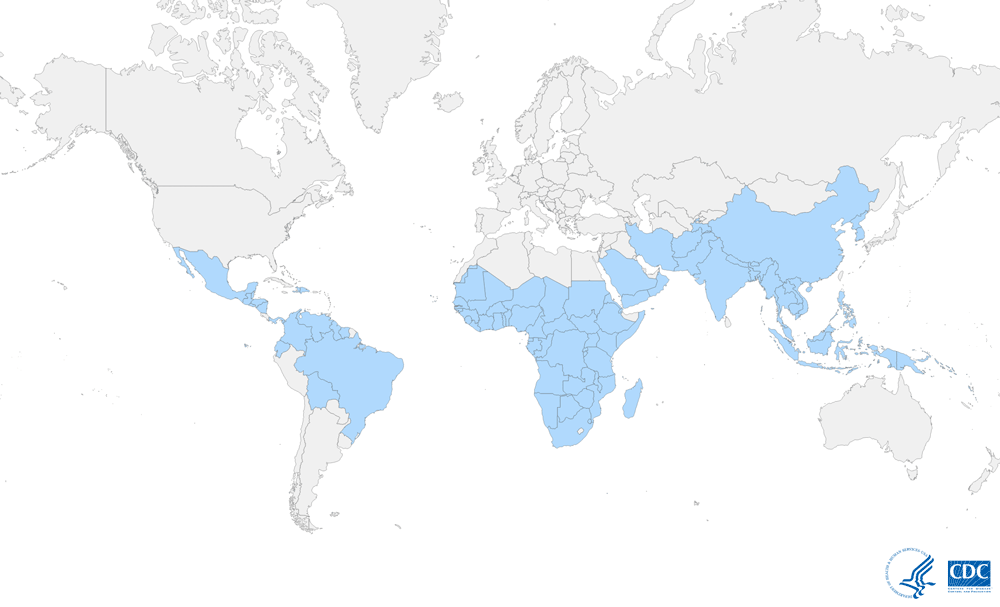

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) says malaria occurs mostly in poor tropical and subtropical areas of the world and is a leading cause of illness and death in those regions. Some 3.3 billion people live in areas at risk of transmission.

Although Africa is home to the majority of cases, the problem exists across the globe, as evidenced by its presence in 91 countries. For example, to the east of the continent, CDC maps show malaria is prevalent across South Asia. That includes all of Laos, Bangladesh and India (except at higher elevations), and much of Cambodia and Pakistan (below 2,500 feet altitude). It is also present in areas of eastern Indonesia and some areas of Thailand, Vietnam, Burma (Myanmar) and Papua New Guinea.

Even in the United States, which largely eradicated the problem in the early 1950s, the CDC says 1,700 cases are diagnosed annually. The majority are among travelers and immigrants returning from countries where transmission occurs, many from South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. There were also 63 outbreaks of locally transmitted, mosquito-borne malaria between 1957 and 2015.

This fight goes on despite the awarding of five Nobel Prizes in physiology or medicine for work associated with malaria between 1902 and 2015. Small wonder that a National Institutes of Health researcher once commented, “In its ability to adapt and survive, the malaria parasite is a genius. It’s smarter than we are.”

Spotlight on World Malaria Day

It isn’t just WHO focusing attention on malaria. In January, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (long involved in anti-malaria causes), the Inter-American Development Bank and the Carlos Slim Foundation announced they would provide a collective total of $83.6 million in new funding to combat malaria in seven nations in Central America and the Dominican Republic.

The Regional Malaria Elimination Collective is also aimed at ensuring malaria treatment remains a health and development priority. The funds are to help leverage more than $100 million in domestic funding and $39 million of existing donor money by 2022. Although Central America has seen a 90 percent drop in cases since 2000, “progress against the mosquito-borne disease has stalled and several countries in the region still have significant problems with malaria,” reported Reuters News Service in late January.

These developments occur amid the upcoming World Malaria Day (Apr. 25), which has been an annual emphasis since 2007. The international observance was established by WHO’s decision-making body to provide education and understanding of the disease and to spread awareness of strategies to curtail its spread.

On its first year, former President George W. Bush designated Apr. 25 as “Malaria Awareness Day” and called on Americans to join the effort to eradicate the disease on the African continent.

Among the initiatives announced were a $3 million challenge grant from ExxonMobil, a fundraising promotion by Major League Soccer, a challenge by Pastor Rick Warren to 300,000 churches to take on malaria as a cause, and a campaign against malaria by the Boys and Girls Clubs of America.

A number of countries participate, spanning such nations as the U.S. to Germany to India, Nigeria and Uganda. In addition to governmental action, businesses, non-governmental organizations and individuals use the day as an opportunity to engage in fundraising, while many media outlets help publicize public awareness campaigns.

World Malaria Day helps shine a spotlight on prevention, a crucial strategy in reducing the incidence of the disease. WHO says that since 2000, this has played a key role in reducing cases and deaths, with the indoor spraying of insecticides and distribution of insecticide-treated nets leading the way.

What difference has this made? Across sub-Saharan Africa, just over half the population slept under nets in 2015, compared to less than a third five years earlier. During that time period, preventive treatment for pregnant women increased five-fold in 20 African nations. Globally, new malaria cases fell 21 percent between 2010–2015, while death rates declined by 29 percent. However, much remains to be done.

WHO’s global technical strategy has a goal of a 40 percent reduction in malaria cases and deaths by 2020, but less than half of the countries facing the threat are likely to meet that target.

Indeed, Dr. Abdisalan Noor, team leader of WHO’s Global Malaria Program Surveillance Unit, says the declining trend in malaria cases and deaths has slowed and even reversed in some regions over the past three years.

In commenting on the 2017 World Malaria Report issued last November, Dr. Noor said there are continued gaps in coverage of basic prevention, diagnostic and treatment tools.

“As noted in the report, less than half of households in countries in sub-Saharan Africa have sufficient bednets, and only about one-third of children in the African Region with a fever are taken to a medical provider in the public health sector,” he said.

Indeed, Dr. Abdisalan Noor, team leader of WHO’s Global Malaria Program Surveillance Unit, says the declining trend in malaria cases and deaths has slowed and even reversed in some regions over the past three years.In commenting on the 2017 World Malaria Report issued last November, Dr. Noor said there are continued gaps in coverage of basic prevention, diagnostic and treatment tools.

“As noted in the report, less than half of households in countries in sub-Saharan Africa have sufficient bednets, and only about one-third of children in the African Region with a fever are taken to a medical provider in the public health sector,” he said.

Combatting a Tough Disease

Malaria has a history extending back thousands of years. The legendary Greek doctor, Hippocrates (born in 460 B.C.), described periodic fevers. It was so common in the Roman Empire that one report said it may have contributed to the empire’s decline. At one time, it was also common across Europe and North America.

Malaria needs a combination of high population density, high anopheles mosquito density, and high rates of transmission from humans to mosquitos and vice versa. If any of the factors is lowered sufficiently, the parasite will eventually disappear from the area. However, unless eliminated entirely, it can be re-established if conditions revert to a combination favorable to the parasite.

The battle against the disease has raged for centuries. Scientific studies on malaria saw their first major advance in 1880, when a French army doctor working at a military hospital in Algeria observed parasites in the red blood cells of infected patients. Alphonse Lavern suggested that malaria was caused by this organism, which along with other later discoveries, earned him the Nobel Prize in 1907.

More than a century later, the battle fighting malaria continues. It is expensive. According to one report on research and development challenges in the health field, one drug costs $150–200 million and seven to 10 years to develop, one vaccine costs $600–800 million and takes 10–15 years, one diagnostic costs up to $50 million and takes three to five years, and one vector control product takes $60–65 million and 10–12 years. It projects the annual research and development need for malaria over a decade ending in 2022 will range from $5.5 billion to $8.3 billion.

Still, it is a war worth waging. Not only can severe cases cause lifelong intellectual disabilities, but its economic impact can cost billions of dollars annually in lost productivity. WHO says certain population groups are at higher risk of contracting malaria and developing serious disease: children under 5, pregnant women, patients with HIV/AIDS, non-immune immigrants, and mobile populations and travelers.

To date, vaccines have been lacking, but WHO hopes Mosquirix™ will prove to be a game changer. It will be administered to at least 360,000 children in areas of Ghana, Kenya and Malawi, with some regions selected for participation to serve as comparison groups to areas where the vaccine will not be available initially.

Developed by the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative and GlaxoSmithKline with support from the Gates Foundation, Mosquirix™ was engineered with genes from the outer protein of a malaria parasite, a portion of a hepatitis B virus, and a chemical component to boost immunity. The vaccine works to prevent infection by blocking the parasite from infecting the liver.

Although WHO has yet to make a policy recommendation for large-scale distribution beyond the pilot program, it saw some encouraging—though limited—results in a five-year-long trial (phase three of the program).

“In its ability to adapt and survive, the malaria parasite is a genius. It’s smarter than we are.”

The trial, which concluded in 2014, enrolled approximately 15,000 infants and children in seven sub-Saharan nations. Among participants who received four doses, the vaccine prevented approximately four in 10 cases of malaria (39 percent) over four years of follow-up and just over three in 10 cases of severe malaria (32 percent). Significant reductions were seen in overall hospital admissions and those for malaria and severe malaria.

It will be evaluated for use as a complementary tool, along with the preventive, diagnostic and treatment measures WHO recommends, such as indoor residual spraying with insecticides and the use of anti-malarial medicines.

Challenges Ahead for Fighting Malaria

Progress has been made in the past. WHO’s long-term strategy report, which outlines steps to attack the problem by 2030, says between 2001–2013 an expansion of intervention contributed to a 47 percent decline in mortality rates worldwide. That meant an estimated 4.3 million fewer deaths.

Still, malaria remains a persistent foe. The ability of parasites to evolve and develop resistance is one of the leading challenges. According to one report, a particular class of parasites has demonstrated the capability—through the development of multiple drug-resistant forms—for evolutionary change, which can affect the efficiency of vaccines and other treatments.

Such possibilities surfaced recently in the United Kingdom. Like the U.S., the UK is largely malaria-free but still sees about 2,000 cases annually among travelers returning from other nations. In early 2017, researchers found a drug commonly used in the UK that had been highly effective at treating malaria, but it had failed to cure four patients who contracted the disease while visiting Africa.

Although the patients recovered after receiving alternative treatment, research by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said the failure was due to strains of the disease showing reduced susceptibility. It was also a possible first sign of drug resistance to a drug known as AL, for artemether-lumefantrine.

Dr. Colin Sutherland, who led the study, told the London Telegraph that treating patients there with AL “might need reviewing.”

“Fortunately, there are other effective drugs available,” Dr. Sutherland said. “(But) frontline doctors should be alert to the possibility of artemisinin-based drugs failing, and assist with the collection of detailed information about specific travel destinations. A concerted effort to monitor AL outcomes in UK malaria patients needs to be made. This will determine whether our front-line malaria treatment drug is under threat.”

In addition, Sutherland told the newspaper that drug resistance is one of the “biggest threats we face” in fighting malaria, and it had already started occurring in parasite strains prevalent in parts of Southeast Asia. Mutations found in genes previously implicated in drug failure in Africa warrant further investigation, the doctor said.

In addition to the medical challenges, there are social and environmental factors. WHO’s 15-year strategy report outlines such problems as social unrest, conflict and humanitarian disasters as major obstacles to progress. So are outbreaks of other diseases, like the Ebola virus in West Africa, which affected countries endemic for malaria and diminished their ability to control malaria.Climate change is another factor.

“Given the association between malaria transmission and climate, long-term malaria efforts will be highly sensitive to changes in the world’s climate,” the report says. “It is expected that—without mitigation—climate change will result in an increase in the malaria burden in several regions of the world that are endemic for the disease, particularly in densely-populated topical highlands.”

In the 2017 World Malaria Report, WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus—former health minister for Ethiopia—termed the malaria response as “at a crossroads.” He said continuing with a “business as usual” approach with the same level of resources and interventions means a likely increase in malaria cases and deaths. “It is our hope that countries and the global health community choose another approach,” Ghebreyesus said in his foreword, “resulting in a boost in funding for fighting malaria programs, expanding access to effective interventions and greater investment in the research and development of new tools.”

Bringing Hope to the World

The fight against malaria has been a multi-faceted one, receiving renewed attention in the late 1990s with the 1998 formation of the Roll Back Malaria Partnership, a global network to coordinate efforts among governments, UN agencies, international organizations and affected countries. Following that, the Global Fund, which fights malaria, AIDS and tuberculosis by providing grants to countries addressing those problems, was established in 2001.

Numerous charities have formed in the wake of these actions; one of the largest is Malaria No More. Its inception came at a White House event in 2006 that launched former President Bush’s malaria initiative. Nothing But Nets is the United Nations’ campaign to end malaria and enjoys broad support. Imagine No Malaria was launched by the United Methodist Church and partners with Nothing But Nets. In addition to raising money for nets, Imagine works on prevention and education, including distributing malaria advocacy kits for churches.

Major Christian ministries are also active in anti-malaria work, such as Samaritan’s Purse, Compassion International and World Vision. The latter’s Malawi arm announced in mid-February that it would distribute 10.9 million treated mosquito nets by the end of 2018 as part of that African nation’s malaria-control program.

“As World Vision Malawi (WVM), we have never undertaken such a mass campaign, but through close collaboration with the Ministry of Health and the Global Fund Country Coordinating Mechanism, we are going to achieve this,” said Charles Chimombo, WVM’s director of programs.

Among lesser-known, but no less effective, efforts on the ground are those by such ministries as Gospel for Asia (GFA). Based in Wills Point, Texas, for more than 30 years Gospel for Asia (GFA) has provided humanitarian assistance and spiritual hope to millions across Asia.

In addition to such services as feeding and educating thousands of needy children, offering free medical care and training, and drilling clean water wells, the ministry distributed 600,000 mosquito nets in 2016.

“In many cases, simple changes can create a profound difference in everyday health,” said K.P. Yohannan, founder and director of Gospel for Asia (GFA). “Christ calls upon us to care for the poor, which is why we are there to offer tools like mosquito nets, which can literally make the difference between life and death.”

One case study of a family helped by such gestures involves a couple named Jitan and Shara and their two children. Living in an area where temperatures commonly soar above 100 degrees for weeks left Jitan, a laborer in the fields, a prime target for the mosquitoes breeding in nearby stagnant ponds and water reservoirs.

In 2015, one of those mosquitoes bit Jitan and injected malaria parasites into his body.

Fortunately, medical treatment (and prayers from Shara and her father) enabled Jitan to recover after three weeks.

Five months later, the Gospel for Asia (GFA)-supported pastor at Shara’s church put her name down as one of 150 recipients for an upcoming Gospel for Asia (GFA)-supported mosquito net distribution. Not only did the fabric mean safety at night from mosquito bites, but to Shara it also symbolized how God saw even their smallest needs.

“My husband suffered with malaria fever,” she said. “Consequently, he is physically weak. But this mosquito net will be protection for my family now.”

The gift touched Jitan’s heart as well.

“Christians not only pray for people, but they also fulfill the basic needs of people in the community,” he said.

One night, as they crawled under the safety of their net, he told Shara: “Really, the Lord Jesus is fulfilling our basic need.”

Strategic Battle Fighting Malaria

When the Gates Foundation adopted its “Accelerate to Zero” strategy in late 2013, it established a core set of foundational principles to make progress toward the goal of eradicating malaria, which it defined as removing the parasites that cause malaria, not simply interrupting transmission.

It sees new drug regimens and strategies as key to that goal, saying clinical cures for individuals do not eliminate the parasites responsible for transmission.

The majority of infections occur in asymptomatic people, who are a source of continued transmission. A successful eradication effort will target such infection through community-based efforts.

Emerging resistance to current drugs and insecticides is a threat to progress, which must guide the use of current tools and development of new ones. And since malaria is biologically and ecologically different throughout the world, strategies must be developed and implemented on a local or regional level.

Nearly five years later, how is the fight proceeding? WHO’s latest malaria report shows some bright spots, such as 44 countries reporting less than 10,000 malaria cases in 2016, compared to 37 nations in 2010.

There is also better access to tools to prevent malaria, such as insecticide-treated bednets, and the testing of suspected cases in the public health sector has increased in most regions. Except for the eastern Mediterranean region, where mortality rates have remained unchanged, all regions reported declines in mortality between 2010–2016.

Yet, despite an unprecedented period of success, Dr. Noor says the corresponding slowdowns in mortality decline in some regions, coverage gaps and lack of medical care have slowed progress.

“Identifying what is behind this trend is difficult to pinpoint,” he says. “In any given country, there may be a multitude of reasons as to why the burden of malaria is increasing. Factors impacting progress could range from insufficient funding and gaps in malaria prevention intervention to climate-related variations.”

In its latest report on malaria, WHO set global targets for 2030 to achieve its vision of a world free of the disease. The three pillars of its plan: 1) Ensure universal access to prevention, diagnosis and treatment, 2) Accelerate efforts toward elimination, 3) Transform malaria surveillance into a core intervention.

Accompanying each target are preceding milestones in 2020 and 2025. The four include:

- Reduce malaria mortality rates globally compared with 2015 by at least 90 percent.

- Reduce malaria case incidence globally compared with 2015 by at least 90 percent.

- Eliminate malaria from countries in which malaria was transmitted in 2015—at least 35 countries.

- Preventing re-establishment of malaria in all countries that are malaria free.

Director General Dr. Margaret Chan said a major “scale-up” of malaria responses would not only help countries reach 2030’s targets but would also contribute to poverty reduction and other development goals.

“Recent progress on malaria has shown us that, with adequate investments and the right mix of strategies, we can indeed make remarkable strides against this complicated enemy,” she said. “We will need strong political commitment to see this through, and expanded financing. We should act with resolve, and remain focused on our shared goal to create a world in which no one dies of malaria.”

Few would argue with those words.

To read more about malaria prevention efforts on Missions Box, go here.

One comment